Throughout my creative life, I have also been involved in book illustration. Since my student years, I have collaborated with leading publishing houses in Kyiv. My book illustrations are always a kind of paraphrase of the author’s text — not essential for the reader, but desirable if the artist’s concept is of interest.

Among the main works in the field of book graphics, I believe the illustrations for Taras Hryhorovych Shevchenko’s poem “Haidamaky” remain significant, as well as a series of illustrations for Carlo Collodi’s fairy tale “The Adventures of Pinocchio”.

The work on “Haidamaky” began as a diploma project at the Kyiv State Institute of Fine Art and was completed in 1992–1993. Remarkably, even then, in the early 1990s, I had a vague yet definite premonition of the coming Ukrainian catastrophe, and I tried to comprehend it as best I could.

Today, this might seem almost unbelievable, but the series of illustrations created more than 35 years ago serves as confirmation. The tragic events in Ukraine at the end of the 18th century are presented here as if seen “from space” — in accordance with Pushkin’s advice: “not to be one-sided, like the French tragedians, but to view tragedy through the eyes of Shakespeare.”

It seems to me that this interpretation allows even Taras Hryhorovych himself to resonate in a new way.

The book was published in 2008 by the Kyiv publishing house “Hrani-T.”

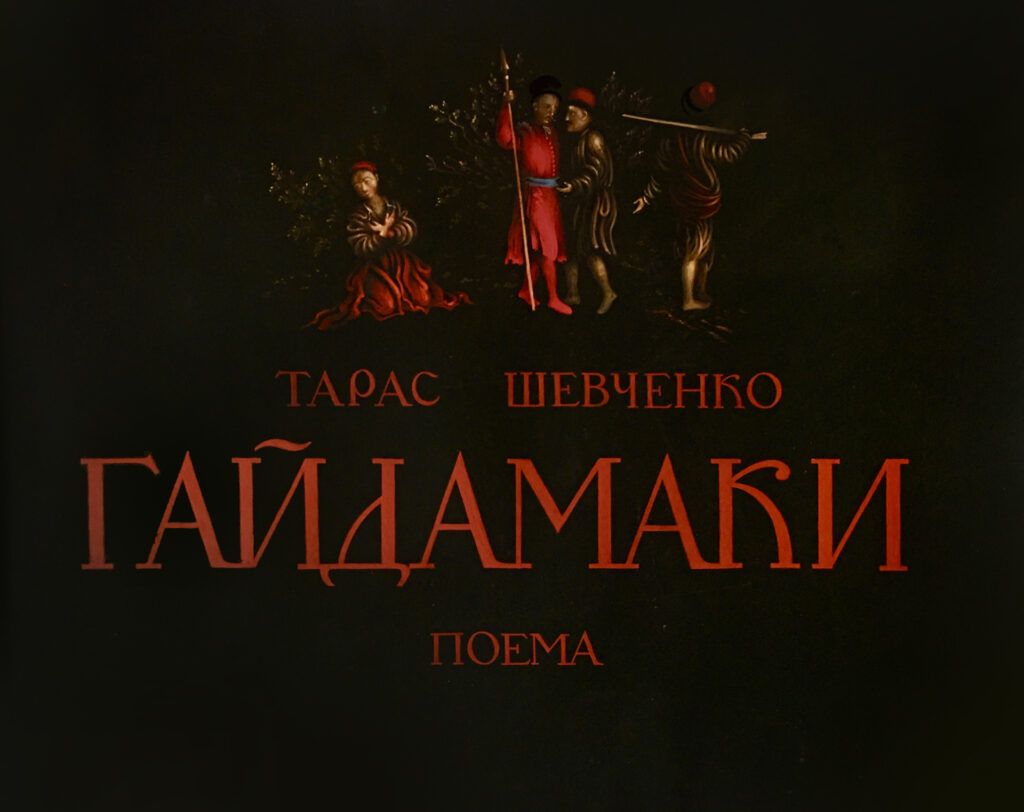

Super Cover to Poem “Haidamaky” by Taras H. Shevchenko

Title Page to Poem “Haidamaky”

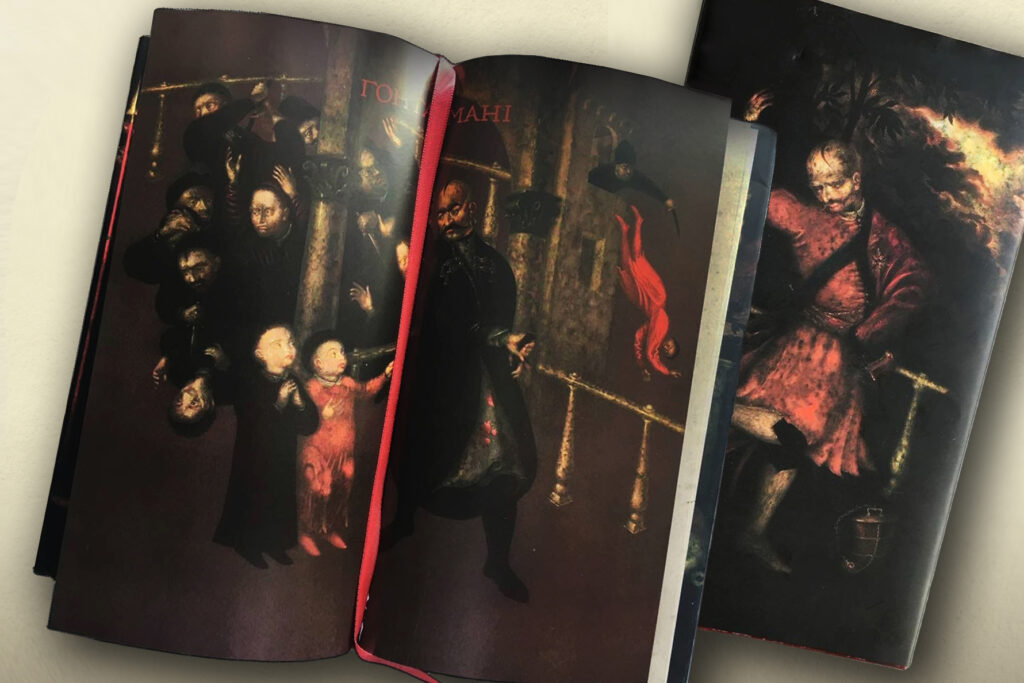

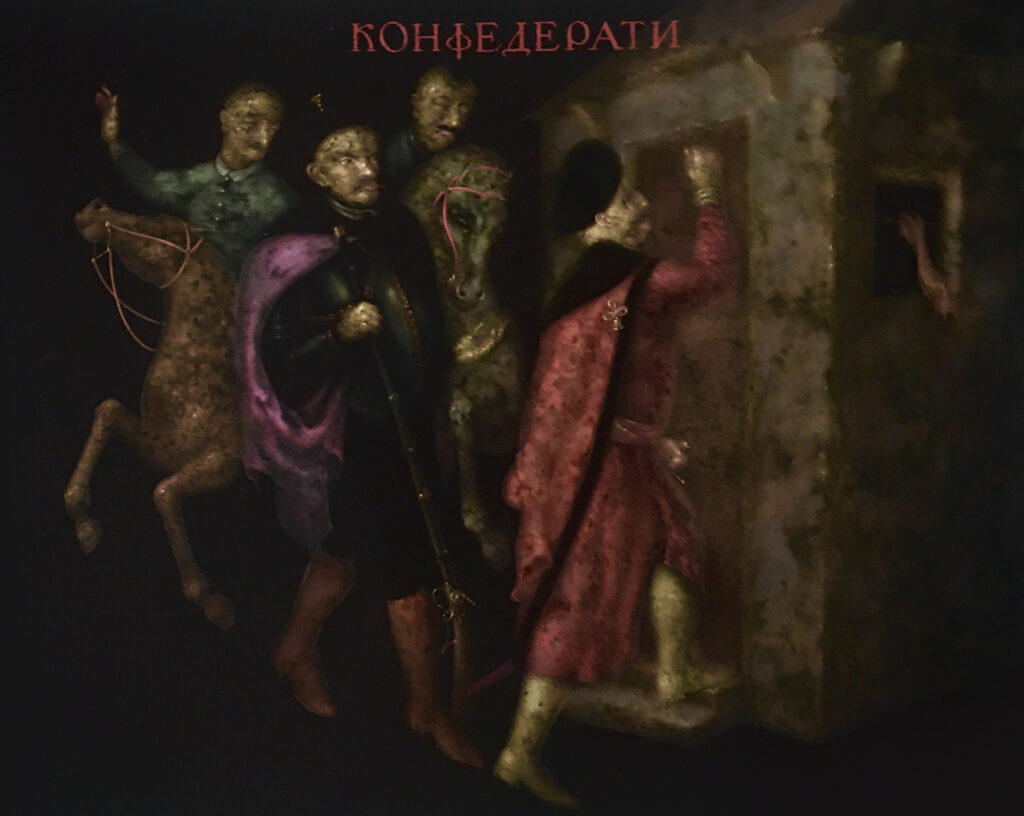

Illustration to Poem “Haidamaky”

Illustration to Poem “Haidamaky”

Illustration to Poem “Haidamaky”

Illustration to Poem “Haidamaky”

Illustration to Poem “Haidamaky”

Illustration to Poem “Haidamaky”

Illustration to Poem “Haidamaky”

Illustration to Poem “Haidamaky”

Illustration to Poem “Haidamaky”

Illustration to Poem “Haidamaky”

Super Cover Fragment to Poem “Haidamaky”

Alexey Kolesnikov about his work on the Poem “Haidamaky” by T.H. Shevchenko

The beginning of work on Pinocchio also has its own backstory.

A long time ago, I happened upon a book by chance, which, if I remember correctly, was titled “The Adventures of a Wooden Puppet”, published in Berlin sometime in the early 1920s. It was a Russian translation of the original Italian, and unfortunately, I didn’t remember the name of the translator. But I do clearly remember the name of the person who edited the translation — Alexei Tolstoy.

I only had the book for a few days — I borrowed it solely to read to my little daughter at bedtime, for educational purposes.

And it all started with her childlike question:

“Daddy, why is she dead? That girl with the blue hair?”

To be honest, I was confused myself — the book felt like it was made of nothing but sharp edges. It seemed overly “mystical” and, to me, not really for children at all. And then I had to return it. But my daughter persistently demanded more of the story, and so I searched my own home library and found a well-worn edition of “The Adventures of Pinocchio” translated by Kazakevich.

Imagine my surprise when I found not a trace of what had so deeply impressed me in that first reading. Before me was the familiar Pinocchio of childhood — exactly the way we all imagine him. It felt like I was reading an entirely different fairy tale.

In the hope of uncovering the origins of that mysterious Berlin text, I turned to the internet. I learned about the extraordinary fate of Carlo Collodi’s famous creation — and about the surprising fact that, despite its immense popularity, there seems to be not a single truly complete edition of this story in existence. Every new translation, every new edition — for a variety of reasons — becomes increasingly softened. Entire fragments are arbitrarily removed from the text, or on the contrary, added.

As a result, the original content — saturated with grotesque, vivid Southern flair, ghosts, coarseness, and incomparable humor — becomes hollowed out, giving way to a kind of sanitized pedagogical correctness.

That was when I had the idea to show the world the real Pinocchio.

With breaks, I worked on the illustrations for over ten years. And I would very much like my Pinocchio to one day find his readers — not at all the way people are used to seeing him. Not smoothed over, but dressed in fantastical rags, and yet — beautiful in all the sharpness of his Pantagruelian outlines.

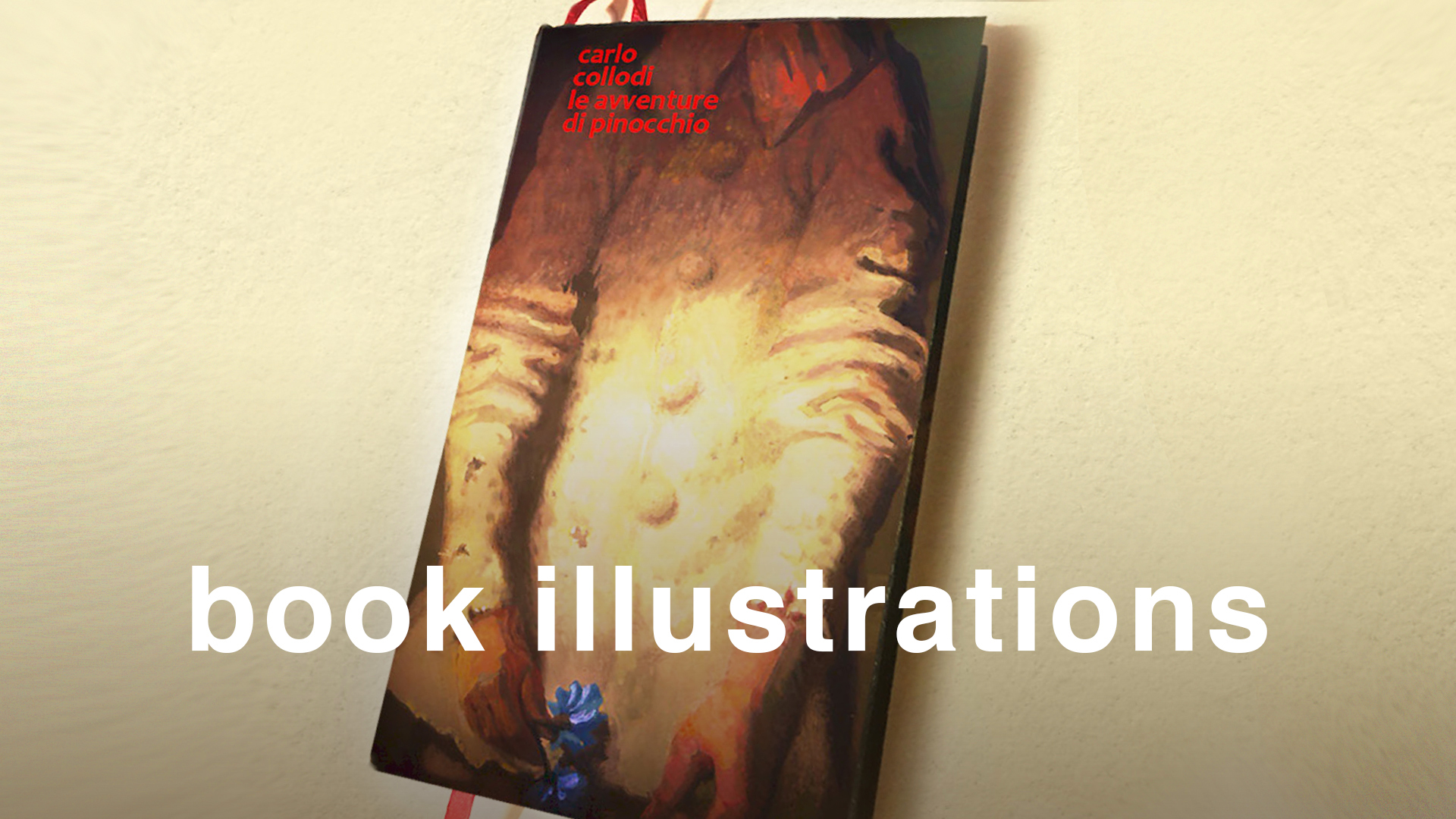

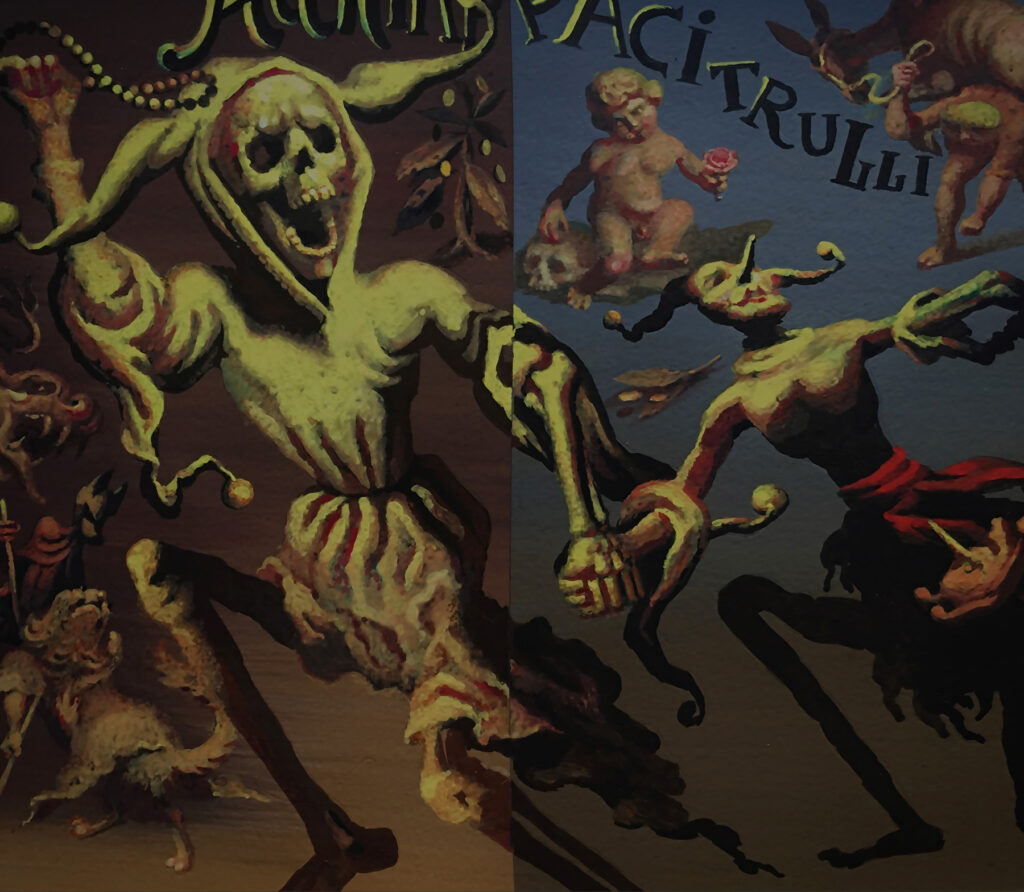

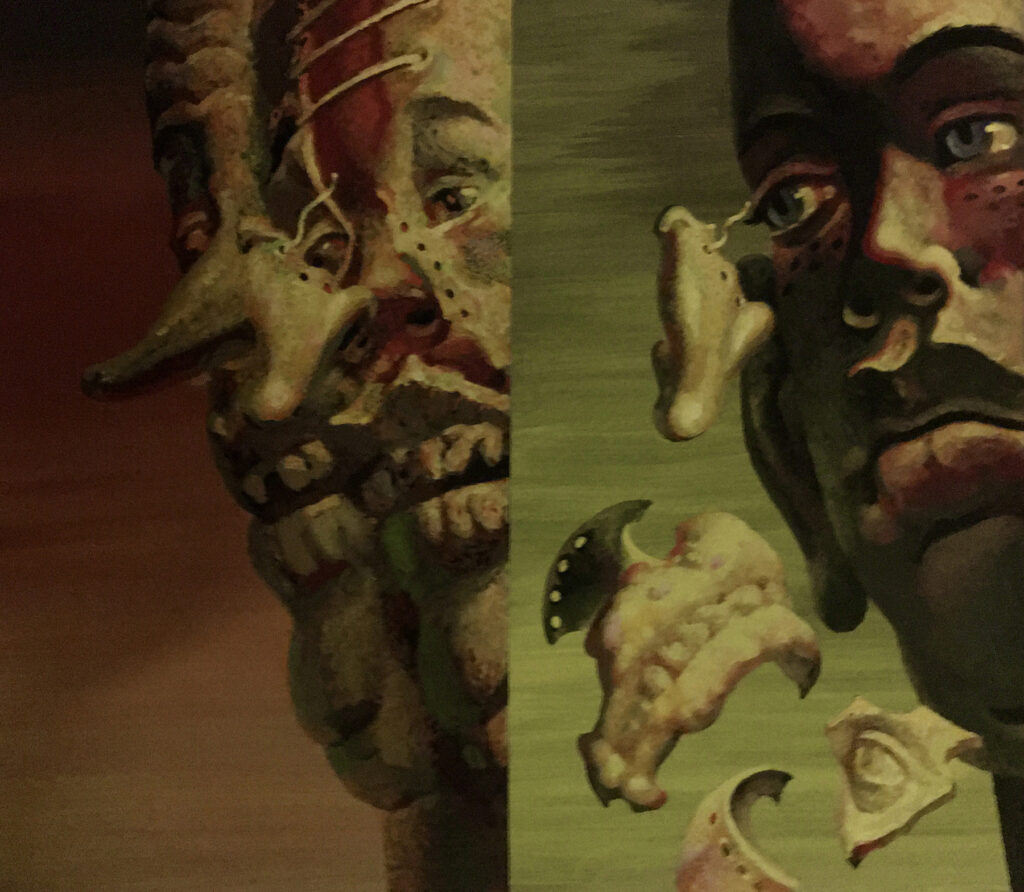

Cover to Carlo Collodi’s

“The Adventures of Pinocchio”

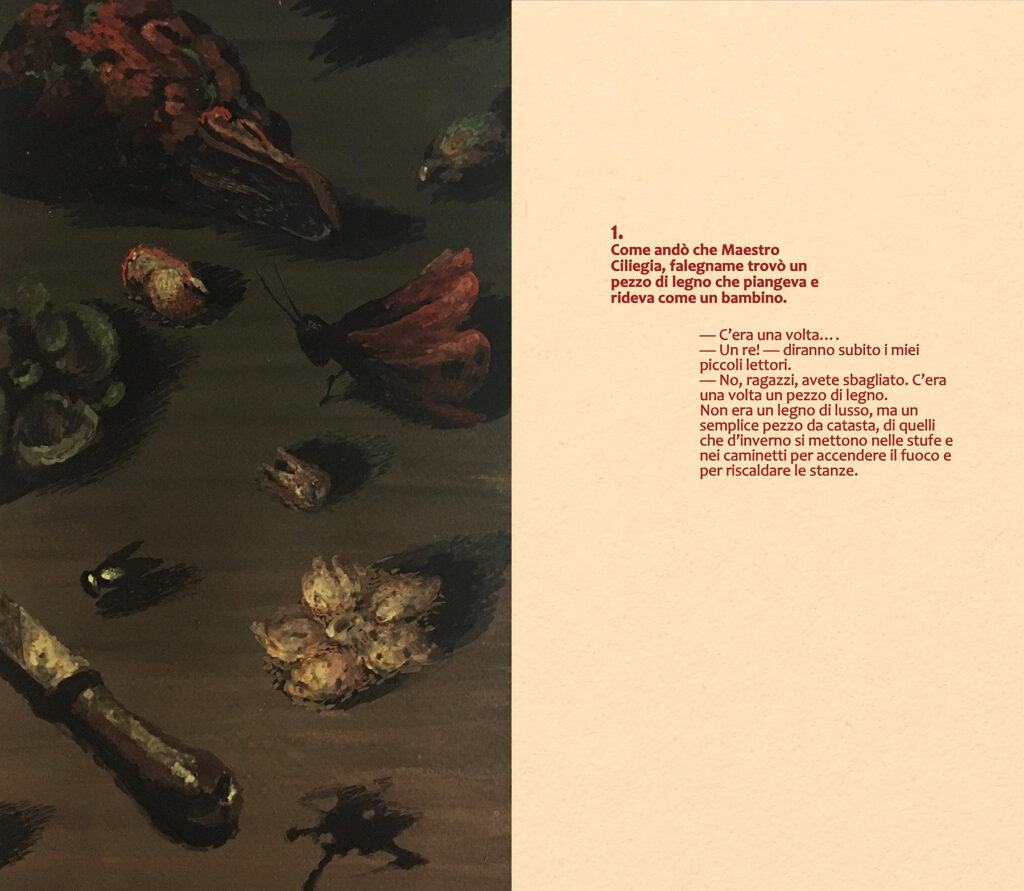

Flyleaf to “The Adventures of Pinocchio”

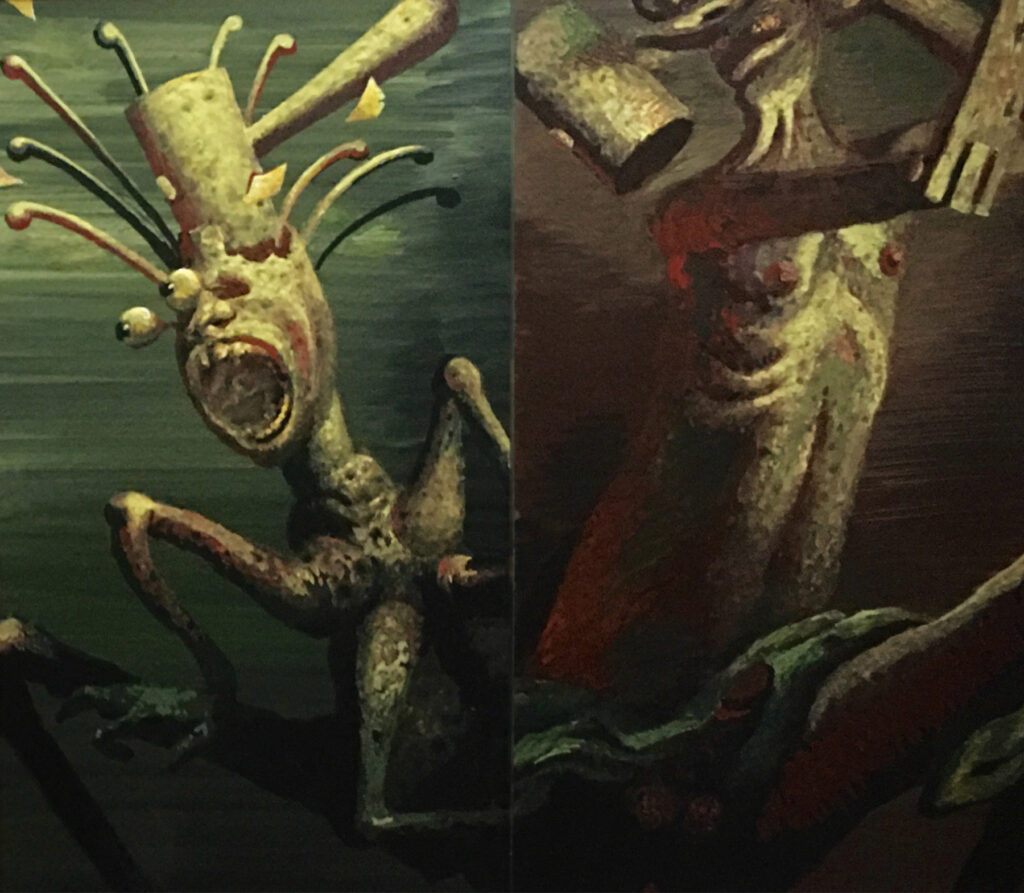

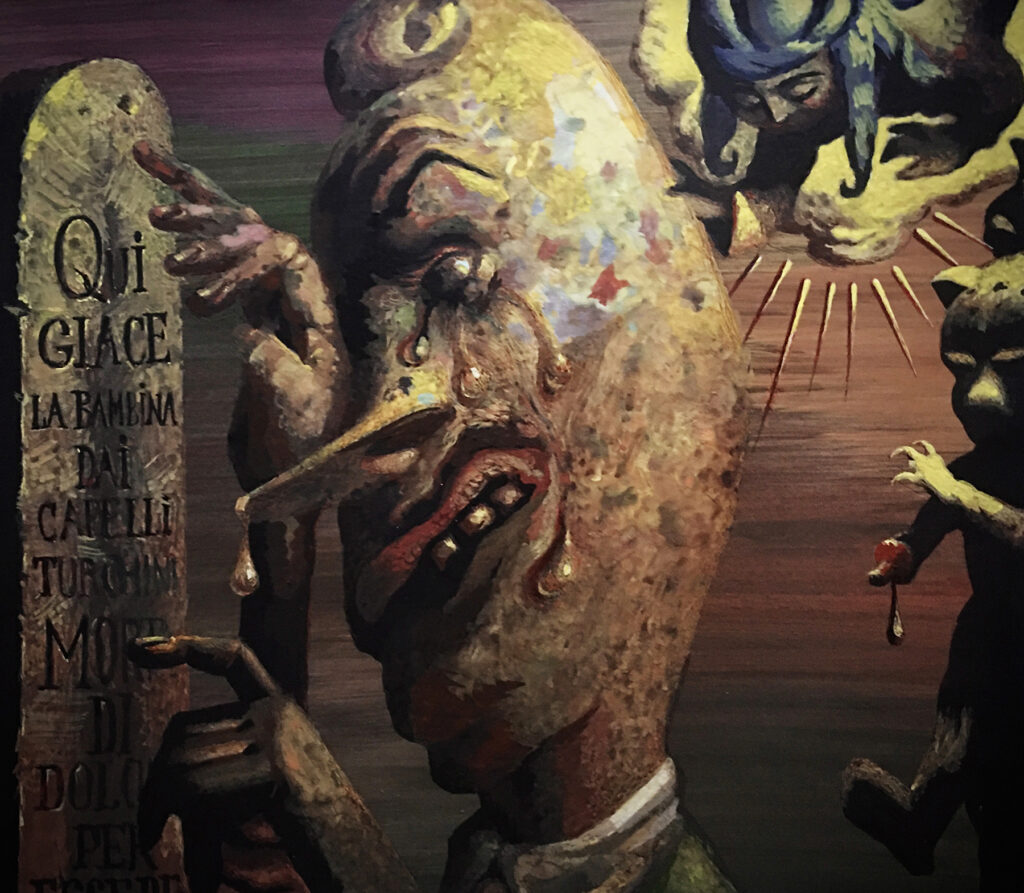

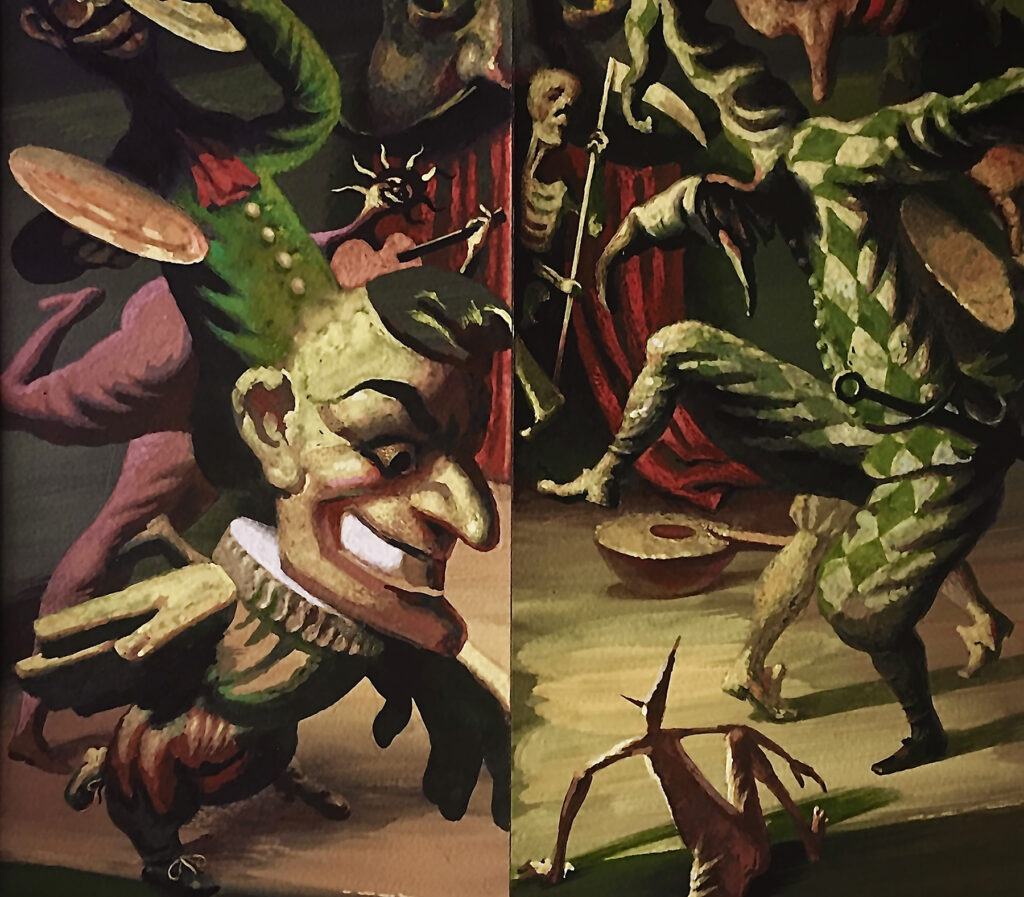

Illustration to “The Adventures of Pinocchio”

Frontispiece to “The Adventures of Pinocchio”

Illustration to “The Adventures of Pinocchio”

Illustration to “The Adventures of Pinocchio”

Illustration to “The Adventures of Pinocchio”

Illustration to “The Adventures of Pinocchio”

Illustration to “The Adventures of Pinocchio”

Illustration to “The Adventures of Pinocchio”

Illustration to “The Adventures of Pinocchio”

Illustration to “The Adventures of Pinocchio”

Illustration to “The Adventures of Pinocchio”

Illustration to “The Adventures of Pinocchio”

Illustration to “The Adventures of Pinocchio”

Illustration to “The Adventures of Pinocchio”

Alexey Kolesnikov on his work illustrating Carlo Collodi’s “The Adventures of Pinocchio”

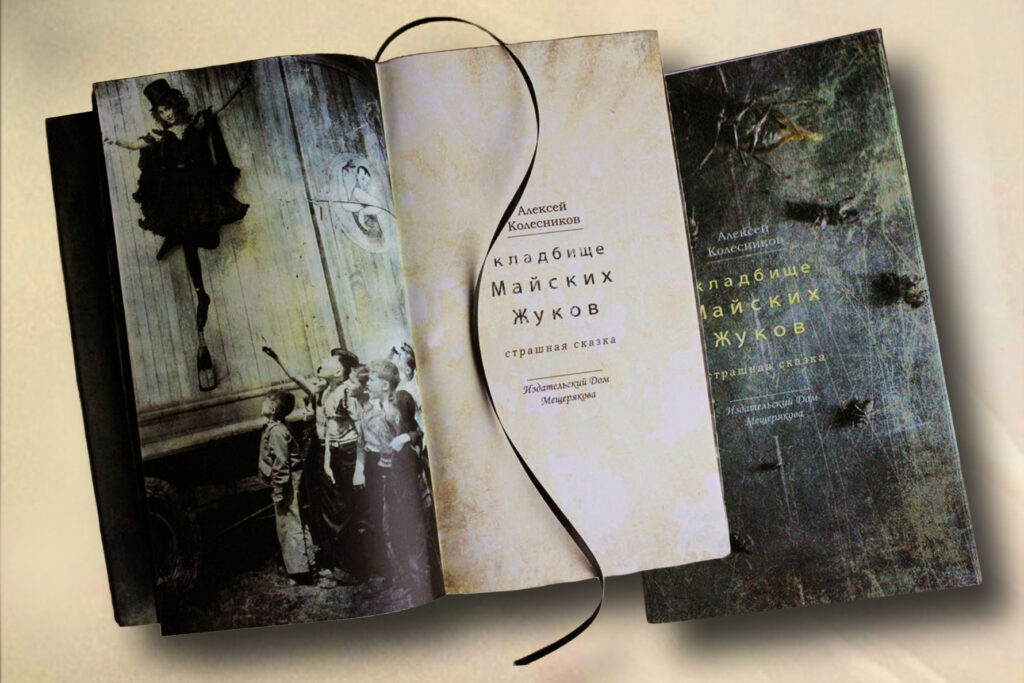

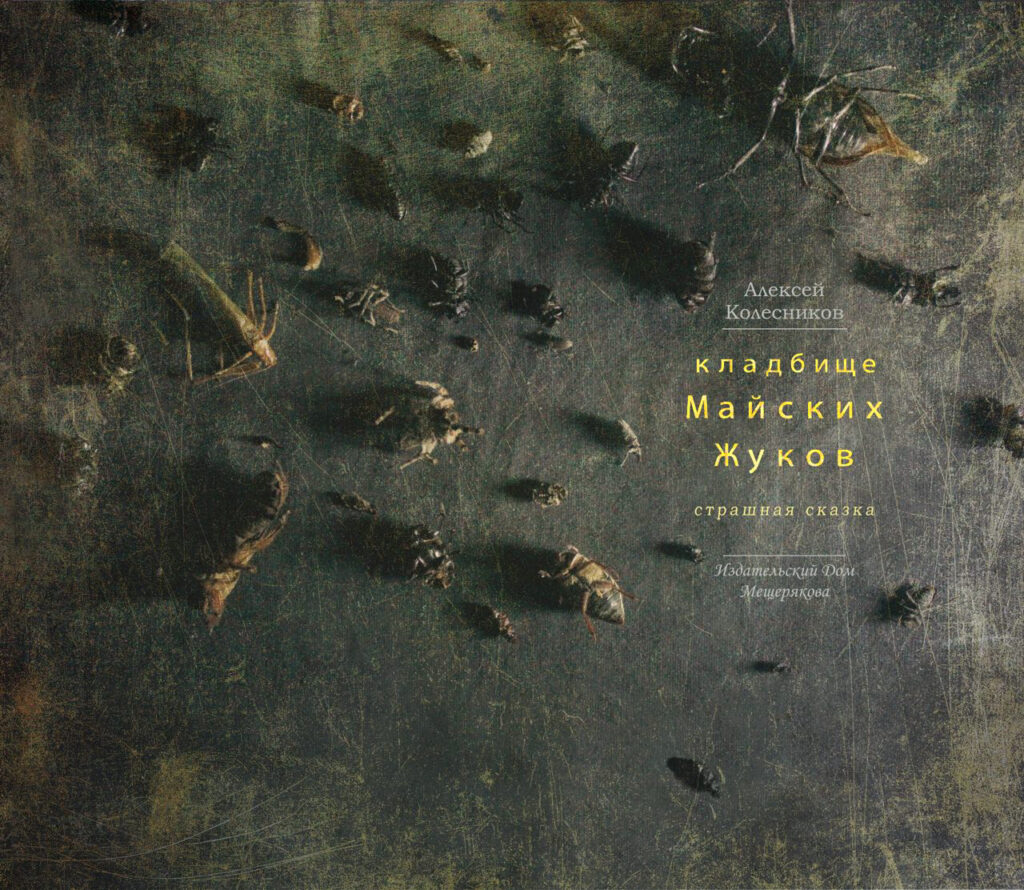

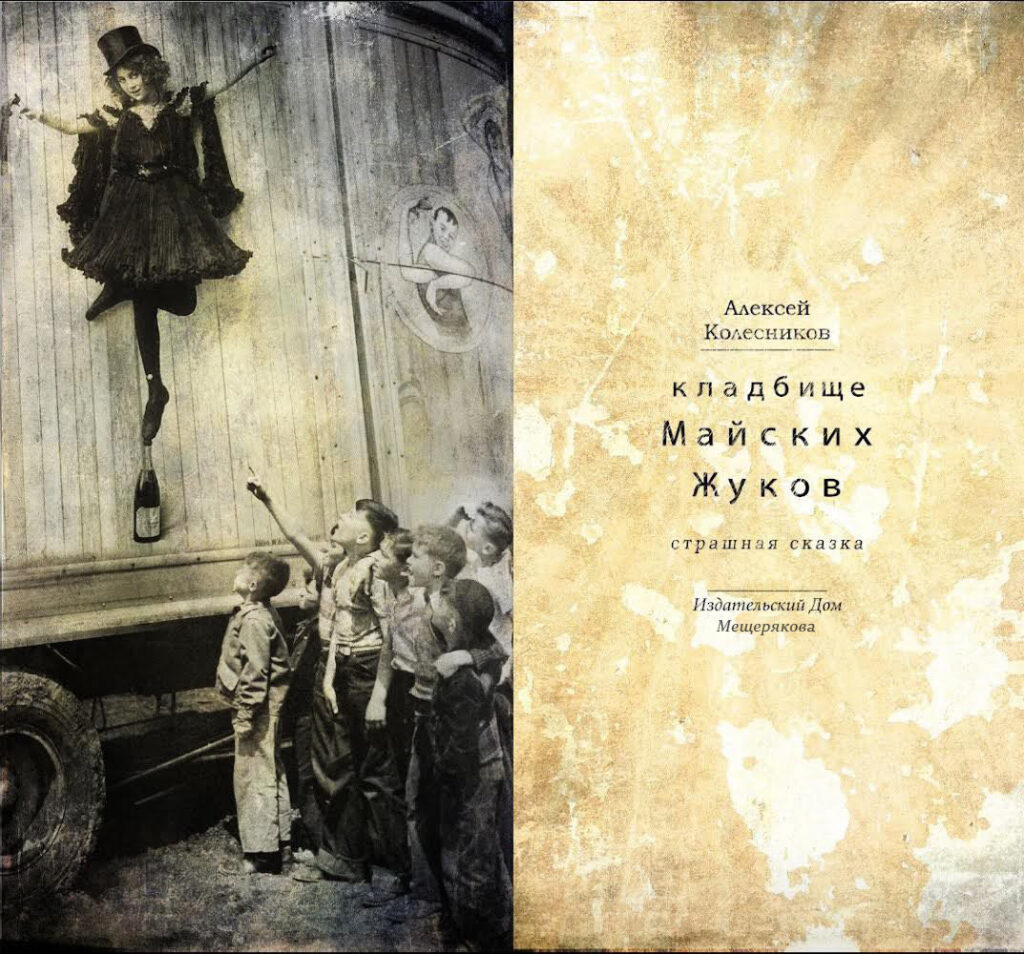

“The Cemetery of May Beetles” – is the first book I created not as an artist, but as a writer. I’ll tell the story of how this text came to be elsewhere. For now, I’ll only mention that, as an artist who has dedicated a significant part of my life to illustrating other people’s books, I simply couldn’t bypass my own. As a result, a layout for the design was created—rejected by the publisher, it’s true, but, in my opinion, still interesting in its own way. In this case, the illustrations are a series of specially processed photographs. The cover photo was created specifically for the book by photographer Alesia Wetstein.

Cover to “The Cemetery of May Beetles”

Half Title to “The Cemetery of May Beetles”

Title Page to “The Cemetery of May Beetles”

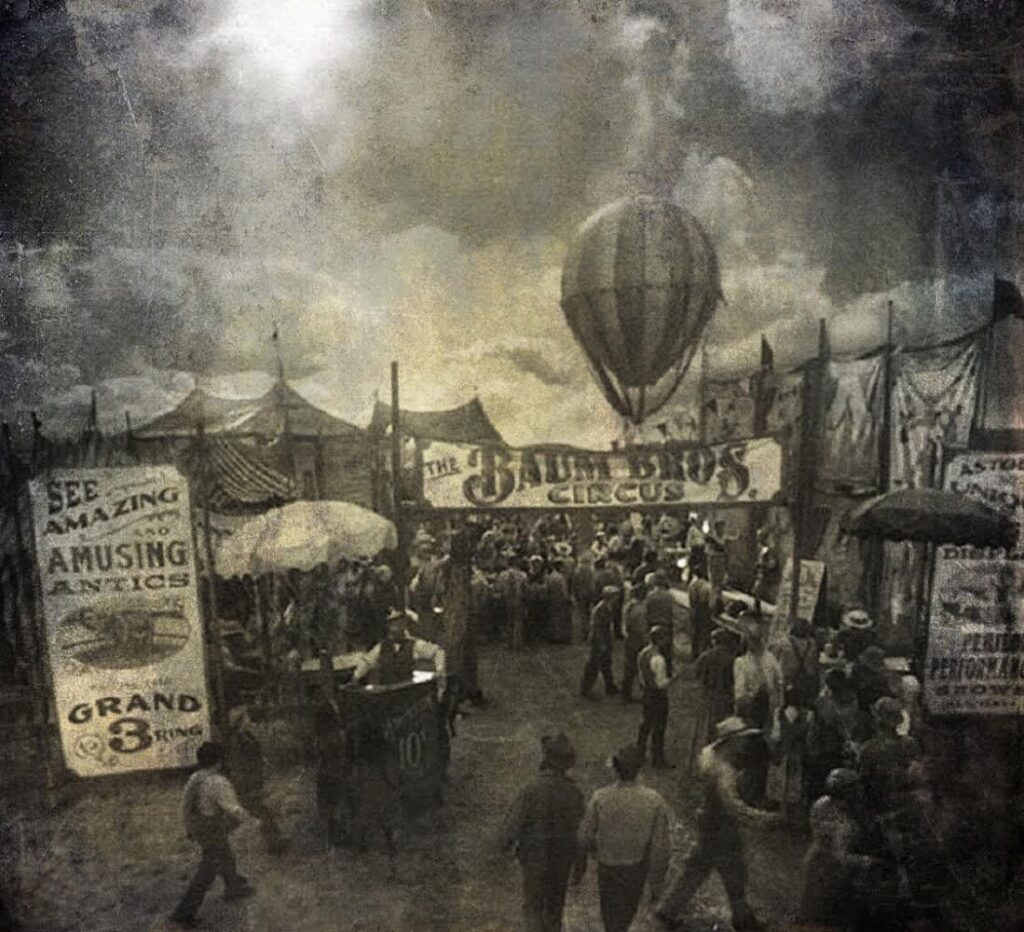

Illustration to “The Cemetery of May Beetles”

Illustration to “The Cemetery of May Beetles”